Russian airspace has been off-limits to most Western carriers since the start of the Ukraine war. For U.S. airlines that means a much less direct route, longer flight times and more fuel burn.

Large swaths of the Middle East are dangerous to fly through right now, given the frequent missile launches we’ve seen. And India and Pakistan went through tit-for-tat airspace bans this year.

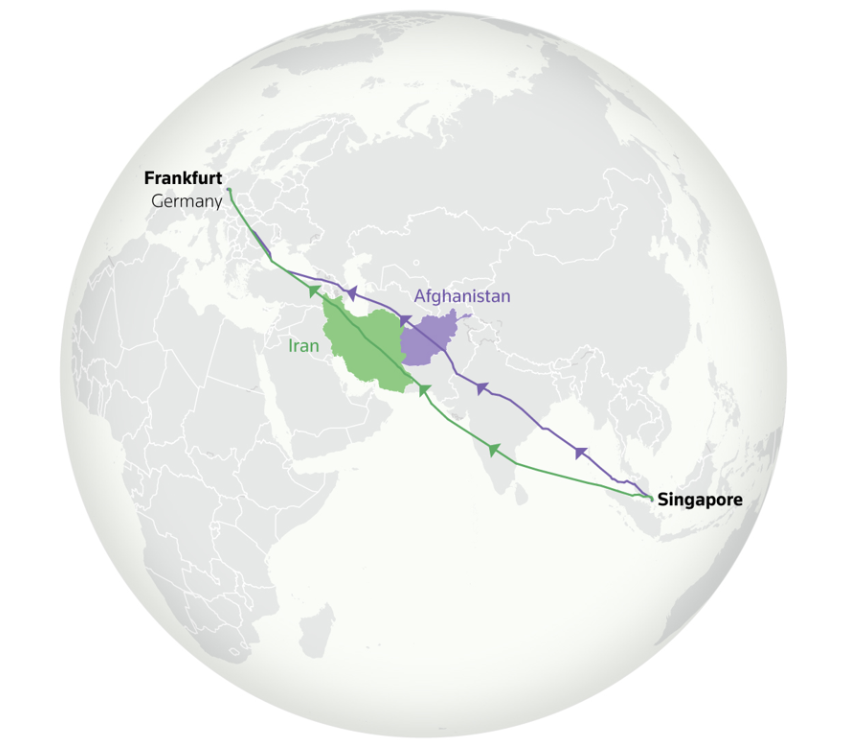

As a result, airlines are running out of viable routes between Europe and Asia. But one safehaven has emerged: Afghanistan. Their skies were once avoided during decades of war but are now relatively low risk (!) with the Taliban offering stability. And many airlines have started routing flights through their airspace (in purple) instead of via Iran (green) or other troubled areas.

Overflights in Afghanistan are up nearly 500% this week as airlines adjust to airspace closures in neighboring Iran and Iraq. https://t.co/0SKeP94D5q pic.twitter.com/EcObuyemw6

— Flightradar24 (@flightradar24) June 20, 2025

The FAA eased its post-2021 restrictions on Afghan airspace in 2023. Airlines had stayed away when the Taliban took over, and air traffic control services stopped. But with missile and drone exchanges between Iran and Israel those skies became challenging. The FAA now even allows U.S. carriers to use a narrow corridor over northeast Afghanistan (the Wakhan Corridor). And European regulators accept high altitudes as well.

- The FAA currently prohibits U.S. civil operations in the Kabul FIR (OAKX) below 32,000 feet

- but expressly permits overflight on jet routes P500/G500 at or above 30,000 feet in the far-eastern Wakhan corridor through July 25, 2028.

- There’s very little use of this by U.S. cariers, however. United’s India flights may clip the Wakhan corridor. American obtained an FAA exemption to use the corridor at 30,000 feet (P500/G500) but they don’t do so much with their current route network.

- The traffic spike is dominated by European and Asian carriers (Lufthansa, BA, KLM, Singapore Airlines, EVA, China Airlines, Air India, etc.).

The Taliban government glommed onto this change like white on rice. The country is largely surrounded by skies that are effectively closed, and they now get to be a toll booth. Officials in Kabul instituted a flat $700 fee per flight to transit Afghan airspace. It’s the same overflight fee for a widebody as a private jet. And it’s cheaper to pay than to add 500- or 1,000-miles to a flight (and perhaps even be forced ot make a technical stop).

Under the previous U.S.-backed government, fees were lower. About 400 flights a day overflew Afghanistan. And this generated around $280,000 a day.

In 2021 this declined to near-zero for obvious reasons. Now, with traffic back to half of 2020 levels, overflight fees are a revenue driver for the Taliban government.

By mid-2024 only a trickle of flights had returned. Taliban officials acknowledged 100 – 120 overflights daily at $700 apiece or about a $28 million annual run rate. Now they’re netting 2.5 to 3 times that – they’re back to 2019 revenue off fewer flights.

The Taliban govenrment isn’t broadly recognized and faces sanctions. IATA stopped collecting Afghan overflight fees before 2021. So airlines don’t wire them money. Payments are handled through third-parties in the UAE like GAAC which manages Afghan airports and services and other facilitators who secure overflight permits and collect the fees.

Now the process is murkier, without great record-keeping. It becomes something of an honor system, with airlines not even receiving official invoices from the Afghan government.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Treasury has issued guidance allowing these transactions for air navigation services despite sanctions, so paying $700 to the Taliban’s aviation authority won’t land an airline in legal jeopardy.

It’s strange to fund the Taliban for safe passage, but it does align incentives. And British Airways, Lufthansa, KLM, Air France-KLM, Singapore Airlines, Turkish Airlines, EVA Air, China Airlines, Thai Airways, and others appear to overfly the country now.

Most regulators require planes to stay above 32,000 feet over Afghanistan in what I believe is uncontrolled airspace – high enough that shoulder-fired missiles or most anti-aircraft weapons below can’t reach them.

Airlines use published contingency routes and broadcast their positions to each other over a common radio frequency (a procedure known as “TIBA”). I’ve written about rethinking air traffic control along these lines more broadly.

My biggest concern isn’t even an MH17 scenario (shot down by Russian-adjacent forces with surface to air missiles) and more the potential need to make an emergency landing in Afghanistan,without airport radar, weather information, or security on the ground. You don’t want to go mechanical or have a medical emergency where spare parts are scarce and the local healthcare basic at best.

Since reportedly 85% of Afghans live on less than $1 a day, overflight fees are material to the government and economy there. And it’s hard currency that’s difficult for the country to come by. It also projects a functioning government. They may not be recognized, but they’re receiving worldwide air traffic and being paid for it (often by state-backed carriers, in some sense a de facto recognition).

Meanwhile here’s what the Intercontinental Kabul is like and here’s a new Afghanistan tourism video (graphic footage that resembles beheadings, fighters holding Kalashnikovs, and military-style parades):

شاهد الرسالة القوية التي وجّهها شباب أفغانستان إلى الولايات المتحدة!#أفغانستان_بالعربي#افغانستان pic.twitter.com/W3LrrNJy88

— أفغانستان بالعربي (@afghanarabc) July 5, 2025

:

(HT: Enilria)

That’s a nice flight path you got there… would be a shame if somethin’ were to happen to it… *gestures to pay-up*

Very interesting. As you know, a lot of nations collect “overflight” or “air navigation” fees from passing commercial aircraft. Britain is particularly well positioned on the Trans-Atlantic routes to make quite a bit from this. So paying to use Afghani airspace isn’t by itself unusual, but it certainly is an odd situation. And that Wakhan Corridor was drawn to keep the British in the (Indian) Raj and the Czar’s expanding Central Asian empire separated by a neutral zone. So it’s fascinating how a 19th century political decision for ground based troops shows up again in 21st century aerial commerce.

If you have a medical emergency, landing in Kabul isn’t going to help you much. It’s either Lahore or Islamabad in Pakistan or Baku, Azerbaijan or die.

The next Trump shakedown. If foreign carriers (or US carriers for that matter) want to use the big, beautiful American airspace (many people have said it is the best airspace in the world), they need to give a 10% stake in the airline to the US. Why should foreign airlines profit off our airspace!?

Don’t all airlines pay overflight fees for most countries?

@derek — Welp, I guess I’ll just die then. Wonder if even when the US had an active military presence and air superiority there, whether there were ever any emergencies landed at Bagram, Kandahar, or Jalalabad, or would even that have been too much of a security/intelligence risk.

One of many compliments of Sleepy, Creepy, Joe Biden. The most abysmal foreign policy the world has ever seen. If you vote democrat you own part of it.

Didn’t the US win the war?

@Mike US airlines currently pay to fly over Mexican and Canadian airspace. Your TDS is showing for an article that has nothing to do with the President.

Speaking of Afghanistan, there was supposedly a pretty bad earthquake there recently, near Jalalabad. As with recent earthquakes in Myanmar, I’d imagine their ‘government’ will not handle such an incident well, no matter how much money they pull in from these flights…

TL;DR – Don’t negotiate with terrorists.

Whether it’s the Taliban insisting that freedom to transit airspace doesn’t include financial freedom, Brendon Carr insisting that humor is ok so long as it doesn’t make Trump look stupid, or Russia unilaterally declaring a missle test area of such an immense range (larger than North and South Korea together)…

…it’s up to the bully targets to stand up to the bully. This pussy-ass “Oh hey NATO countries feel free to shoot Russian planes” or “Avoid their airspace” or “pay the taliban” is just curtseying to the bully.

Time to stand up and fly normally, and if there’s any hint of funny stuff, bomb the bullies to oblivion.

Sucking up to Hamas for two years hasn’t release hostages. Sucking up to Russia hasn’t got peace in their blatant attack on the Ukraine. Sucking up to the Taliban (“But hey now we want Bagram airbase back!”) is useless.

The “free world” is full of victims and the bully warlords smell fear and are using it.

Not sure HOW this relates to view from the wing, because I don’t want to see a Buq out my wing-view (shittiest view seats on the flight) but it’s also not my site.