American Airlines employees are still trying to sue over new uniforms that were adopted 10 years ago. Oral argument was held at the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals trying to overturn the dismissal of a case originally brought by 70 employees.

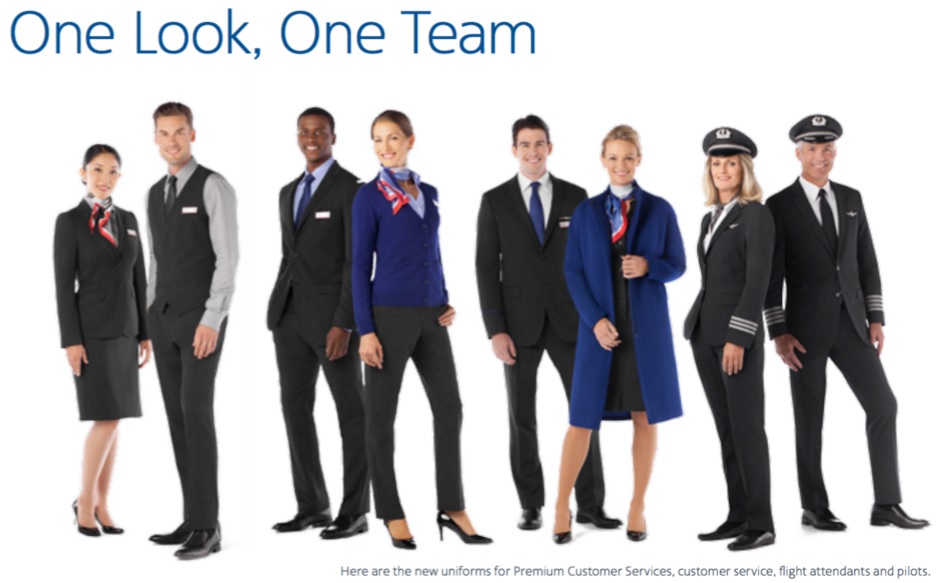

In 2016, American moved from the old blue uniforms to grey uniforms from Twin Hill. And a number of employees reported reactions. They claimed that prior similar issues with Twin Hill uniforms at Alaska Airlines put American on notice to the problem, and pilots had reported rashes and other symptons during a field test prior to rollout, but the airline pushed forward anyway. American’s internal log data reflected ~2,000 – 2,500 calls related to irritation and reactions.

Testing founds most chemicals unlikely to cause reactions, flagged some as potential irritants, and as with most such things concentration matters (‘dose makes the poison’).

Once the uniforms rolled out and complaints escalated, American had Intertek test 123 Twin Hill garments plus legacy uniforms and off-the-rack retail items. Intertek found potential sensitizers across all of them. This testing concluded it was unlikely those unique to the Twin Hill uniforms would cause any of the reported issues, outside of normal range for already-allergic individuals to be sensitive to a given piece of clothing.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found it was possible textile chemicals contributed to skin symptoms for some employees, but testing didn’t identify a chemical responsible. The government concluded that it was unlikely to cause symptoms.

American quickly let employees resume wearing old uniforms and buy off-the-rack substitutes. They terminated their contract with Twin Hill and hired other manufacturers like Lands’ End.

Last April, a district court issued summary judgment against the employees, holding:

- Key dependent experts were inadmissible, not rising to the level of science required by the law

- And without those experts, what remained was testing and complaints that couldn’t show a causal link between uniforms and irritation.

One expert tried to infer causation from correlations between rollout and complaints, and combine that with testing that found there were irritants in the clothes. But they had no theory explaining how a given dose of a specific chemical caused symptoms. The testing did not suggest actual irritation and that identified concentrations were unlikely to be the cause.

Their other expert argued that the chemicals found came from a defective manufacturing process and had no legitimate manufacturing role. But he didn’t offer causality either. And he had conceded that chemicals he claimed had “no purpose” can be standard textile processing components or serve as dye assistance, solvents, or water-repellant finishes. So the court wouldn’t allow his claim that identified chemicals were per se a defect.

The plaintiffs argued that circumstantial evidence of a uniform change and reported reactions should let a jury infer defect and causation, even without identifying a checmical and dose.

Defendents here argue that an expert methodology is needed, testing found the chemicals found weren’t likely to cause issues, and the government couldn’t identify a responsible chemical.

The uniform case, therefore, fails Rule 702 – when a witness gets to testify as an expert and offer opinions and not just facts. This keeps technical-sounding speculation away from juries. A judge has to be satisfied that:

- The person is qualified

- Their education, training and experience fits the specific question

- The opinion will help the jury

- It addresses something the jury can’t reliably figure out on its own.

- And is grounded in data and facts (not thin, cherry-picked) using a legitimate method

The uniforms at issue here were replaced with new ones again in 2020.

I’ve never known quite what to make of the 2016-2017 uniform complaints. It’s something that’s happened at other airlines before. With large numbers of employees some have reactions to what they’re assigned to wear. People started hearing of complaints and noticing that they felt uncomfortable, too. The uniforms became a common culprit for myriad maladies. At the same time there were probably some core of people that were having some issues, but it’s hard to overstate how big a deal this was at the airline at the time. I just hadn’t realized lawsuits were still ongoing.

The American Airlines employees in this case were asking the Seventh Circuit to reinstate their suit, arguing that causality here falls under res ipsa loquitur – the thing speaks for itself. Causality can be inferred. No specific theory on what chemical, at what dose, with scientific justification should be needed to bring this to a jury.

We’d typically say, wear someone else’s shoes to describe empathy, but, here, let’s say, wear someone else’s uniform and experience the rash for yourself, judge.

So, yeah, for real, at this point, just have the case, let the jury decide, and ideally there’s finally some closure here, regardless of the outcome.

Justice delayed is justice denied, even in seemingly insignificant cases. Then again, if you to wear something that gave you a rash, I bet you too would feel it was more significant than not.