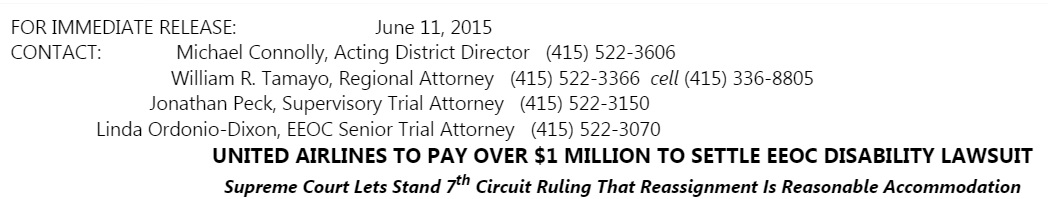

I received a press release this afternoon from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission trumpeting a settlement they secured from United Airlines.

Apparently the airline should have given preference to disabled employees wanting to transfer jobs, rather than to the most qualified candidates for those open positions.

By requiring workers with disabilities to compete for vacant positions for which they were qualified and which they needed in order to continue working, the company’s practice frequently prevented employees with disabilities from continuing employment with United, the EEOC said.

If a disability prevents an employee from returning to work in his or her current position, an employer must consider reassignment. As the Seventh Circuit’s decision highlights, requiring the employee to compete for positions falls short of the ADA’s requirements. Employers should take note: When all other accommodations fail, consider whether your employee can fill a vacant position for which he or she is qualified.

I have several observations on this, none of which are on the merits of the application of the Americans With Disabilities Act. While I have some familiarity with it as an employer, I am not a specialist on the requirements of the ADA.

- The suit was filed in 2009. It was settled in 2015.

- This isn’t United’s first EEOC settlement

- It’s being billed as a settlement of “over $1 million” because it is… $1,000,040. No doubt the EEOC pushed for that extra $40 so they could trumpet the ‘over’ part of the claim.

- The EEOC’s case was dismissed in 2011. However the EEOC got it re-instated by the full 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, arguing that an EEOC case that went to the Supreme Court in 2002 trumped the precedent on which United obtained the dismissal. Given that United had won a dismissal from the 7th Circuit though, it suggests that it at least wasn’t obvious they had been violating the law. In that case, should they be liable, when they couldn’t clearly foresee their conduct was illegal? Shouldn’t the precedent be announced clearly – on a prospective basis – so that employers know what rules they’ll be held to, rather than being pursued for financial penalties based on past conduct?

If I understand your post, there was no finding of a violation of the ADA. The 7th Circuit, en banc I take it, merely reversed a dismissal of the EEOC’s complaint against United and said that the case could proceed to trial through the normal litigation process. It was United’s decision to pay $1 million+ to settle the case now rather than incur the continuing and no doubt substantial costs of litigation and risk an adverse judgment at trial. Any attorney worth there salt can make a colorable claim that his or her client was not violating the law no matter how settled the case law might be. You are either liable or your not. There’s no deduction in damages because it was a 5-4 decision of the Supreme Court. In litigation you pays your money and you takes your chances. Another reason United may have settled is to avoid the possibility of reinstatement of the employees the EEOC was representing. Depending on the number of claimant employees involved, I don’t think $1 million is a big settlement and may represent United’s costs of litigation to obtain a judgment on the merits in the trial court, not to mention any appeals.

I’m certainly no expert either, but the seems to be a bit more complex than simply “disabled employees wanting to transfer jobs”. This ruling is about a current company employee who becomes disabled and unable to do their currently assigned job. In other words, it’s not just about transferring to a new job because they want to. It’s about reassigning them so they can continue to work for the company.

The ruling back in 2012 said that these disabled employees must be appointed to “vacant positions for which they are qualified, provided that such accommodations would be ordinarily reasonable and would not present an undue hardship to that employer.”

Just food for thought…

“I’m not a lawyer but….” is always a great way to start armchair legal analysis.

Your problem seems to be with the existence of the reasonable accommodation requirement, and the goal of integrating people with disabilities into the workplace.

The sentence “Apparently the airline should have given preference to disabled employees wanting to transfer jobs, rather than to the most qualified candidates for those open positions” represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the ADA, and a misrepresentation of the facts involved here.

It should read “Apparently the airline should consider if there is an open position an employee with a disability can perform if their disability makes it impossible to perform their current position, and reassign them to that position if they are qualified for it, even if other employees who do not need reasonable accommodations may also want that open position.”

@Adam amend the end of your sentence though “even if other employees or candidates who do not need reasonable accommodations want the open position and the company has a good faith belief that they would perform at a higher level than the candidate seeking an accommodation.”

But yes, that’s correct.

And in this post I am NOT drawing a conclusion about the law, what it says, or whether it’s the right way to handle such things. My observations are limited to time, framing, and whether United had reasonable notice as to what the law meant in advance in order to have complied.

Gary, First, since you note that there was a 2002 Supreme Court case that supported the reversal of the dismissal, then United and its counsel, had reasonable notice about the ADA’s requirements and cannot claim to be blindsided here. They took a very risky position and lost.

Second, there are no punitive damages or regulatory fines under the ADA to punish an employer, only compensatory damages for the actual losses incurred by employees who are discriminated against unlawfully.

Third, The ADA requires “reasonable accommodation” of a person with a disability except were that would cause an “undue hardship” for the employer. The ADA, its regulations, and court decisions provide notice to employers what that means generally. Obviously, no court or agency can, or should, attempt to spell out for every employer for every disability what is and is not a reasonable accommodation without an undue hardship in all situations. In this case there was the 2002 Supreme Court decision that United chose to ignore.

Fourth, the reversal of the dismissal of the EEOC’s complaint was not a finding of liability it merely said that the case could proceed to determine if the employees were indeed disabled under the Act and if so whether, under the circumstances, the EEOC’s requested relief for the employees was in fact a “reasonable accommodation” that would impose no “undue hardship” on United.

Rather than go through a trial to get the answer, United chose to settle the case for a paltry sum, in my opinion, and without the risk of having to reinstate the former employees.