You’ll Also Want to Be Sure to Read:

- American Airlines Flagship Lounge, New York JFK

- American Airlines First Class, New York JFK – Buenos Aires

- Review: Park Hyatt Buenos Aires

- Eating Around Buenos Aires: Four Notable Meals to Consider

I’m not by any stretch an expert, scholar, or specialist in Argentinian politics. But what I wanted most while in Buenos Aires was to see first-hand some of the political history, to try to gain a better understanding — the country is very much in the midst of transition and instability.

There’s a widening gap between official exchange rates and black market rates, the government has accessed airlines of manipulating the currency, and there are restrictions for instance on the purchase of American Airlines tickets inside of Argentina — no doubt the airline is wary of being stuck in a similar position as in Venezuela where they have had nearly a billion dollars help captive with the government unwilling to allow them to take the cash from the sale of tickets outside of the country.

The case of Venezuela is a fascinating one where citizens could obtain US dollars at the official rate when traveling overseas, and so demand for air travel skyrocketed — you simply could not get seats out of Caracas to the US. In fact, apparently last year the bulk of revenue on American’s San Juan – Miami route consisted of passengers continuing on from Caracas – San Juan, they just wanted to get out of the country and to the US any way they could. It was a profitable endeavor, even at full fare.

Argentina has been following some of the populist rhetoric of their neighbors. It’s a country that seems to see saw between affinity for the U.S. and an anti-U.S. stance. It’s a country government by democratic populists and then taken over by military coup. And it’s a country that has seemingly buried its colonial roots, with few physical landmarks of the era.

The U.S. Supreme Court this year refused to recognize Argentina’s refusal to pay past debts and force creditors to accept pennies on the dollar.

In talking to locals involved in politics it strikes me that they do not view the debts as theirs but as amassed by a previous regime, for its own benefit, and thus not something they ought to have to make good on. They aren’t “Argentina’s” debts, rather each regime — theirs or their opponent’s — governs for its own benefit. And once a new regime takes power, it erases the past, either through refusal to pay debts or by passing laws attempting to undo the work of its predecessor.

In the case of one of the darkest periods in the country’s history, the disappearances of the late 1970s and early 1980s, subsequent governments prosecuted perpetrators, gave amnesty to those same perpetrators, and then sought to overturn that amnesty through the courts.

There’s a battle for the history of Argentina – and to forget its history. Or so it seems to this total outsider. No doubt locals, as well as those with a much better handle on the nation’s poltiics, among my readers will be able to offer their own perspective.

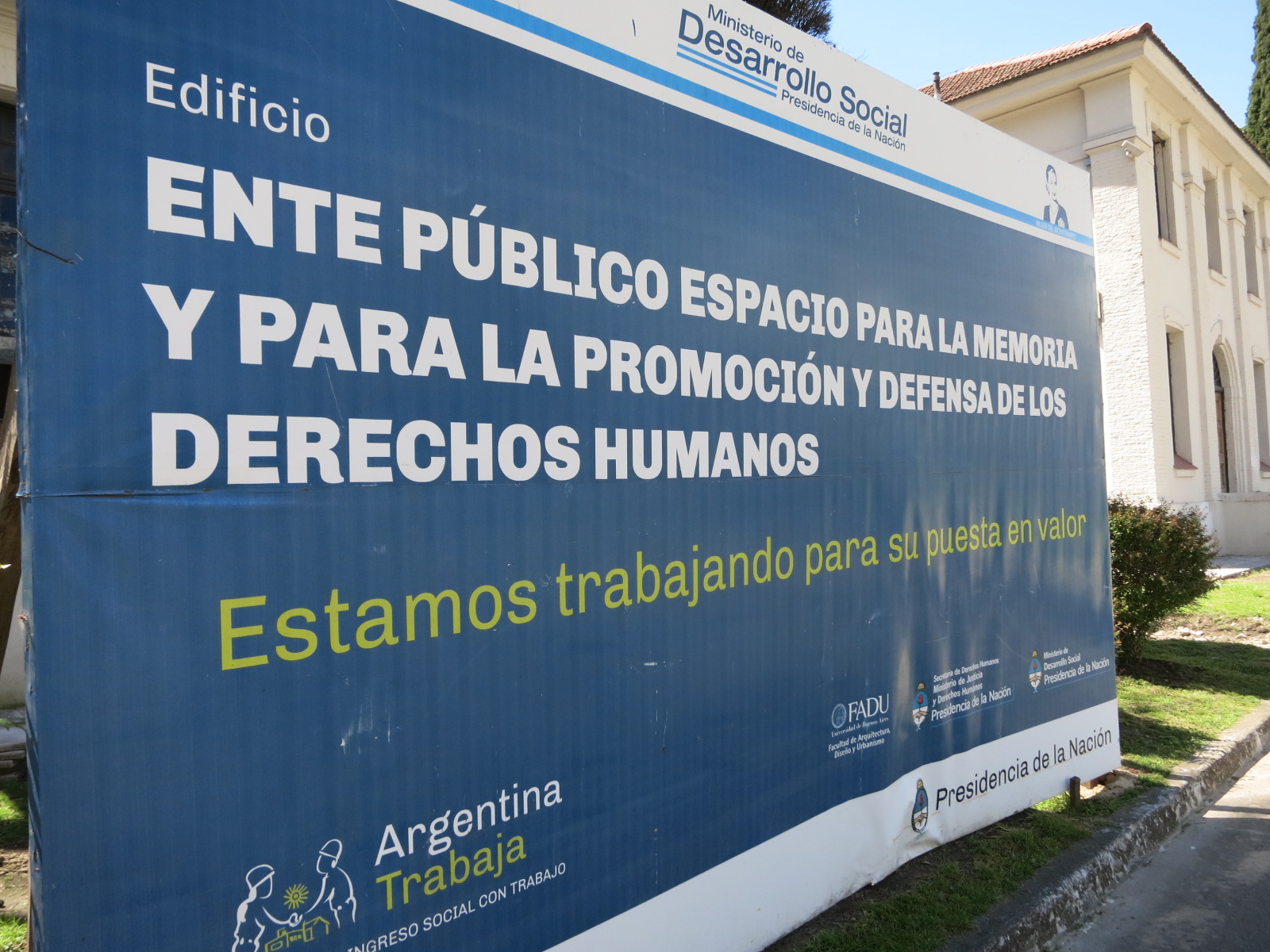

I visited a prison camp close to the city, where many of the disappeareds had been held. It was next to a school, and is now a cultural center. There was very little effort to remember its previous use — there were some signs and artifacts, but mostly the site was about celebrating current life through cultural exhibits.

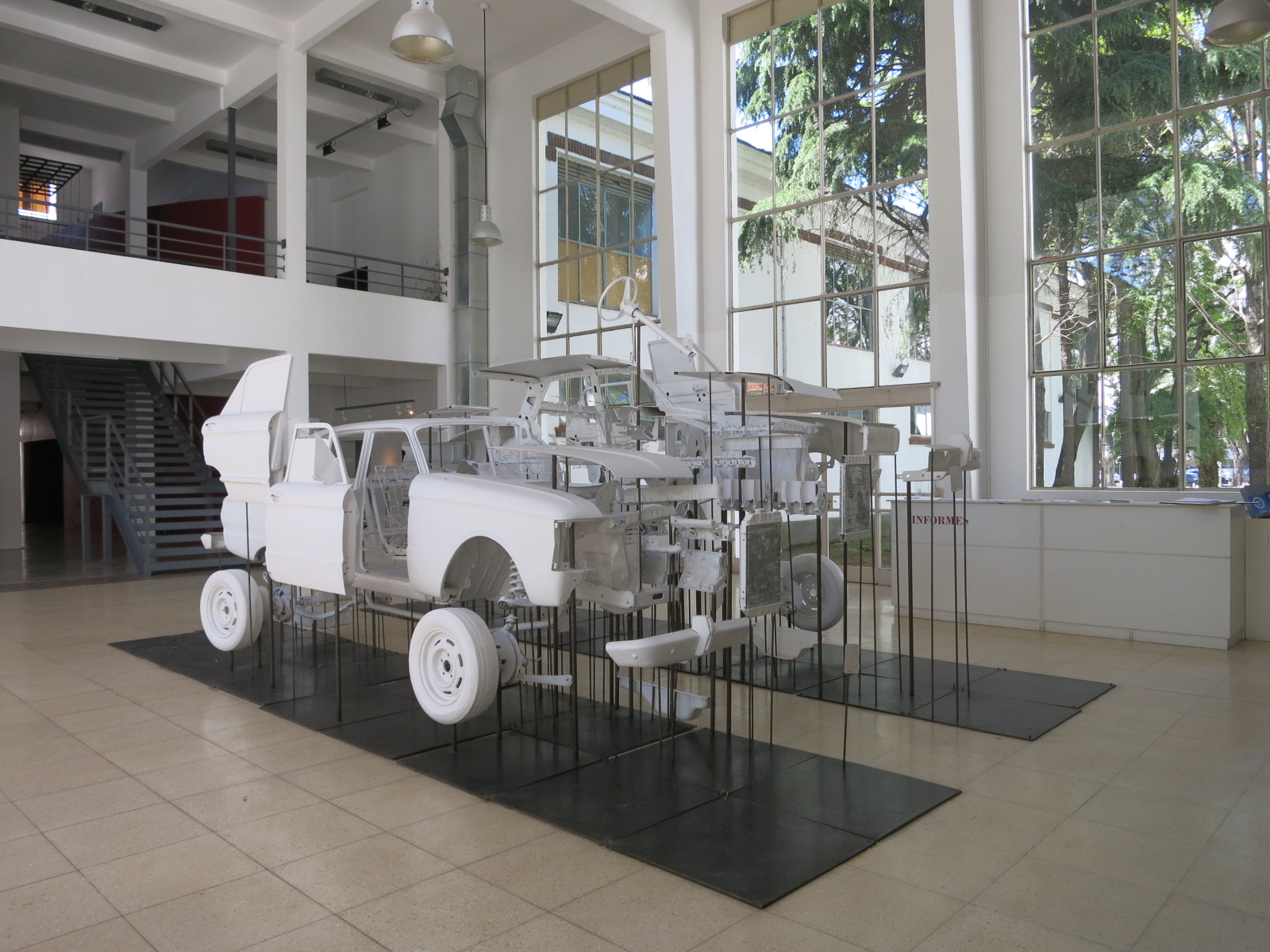

The exhibits themselves though were fascinating, such as this deconstruction of a Ford Falcon — appropriate to the venue because dark green Falcons were the vehicles used by government death squads.

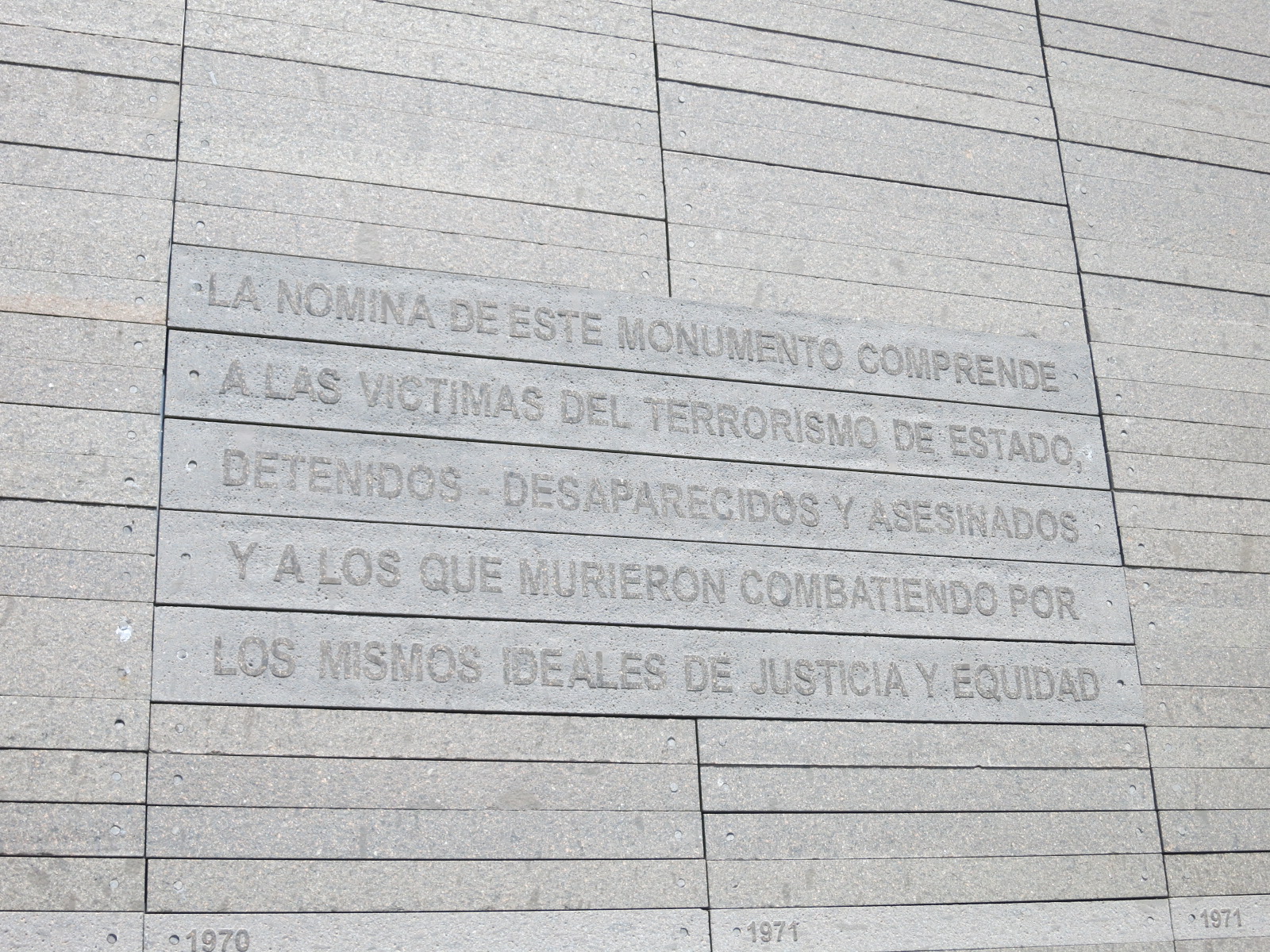

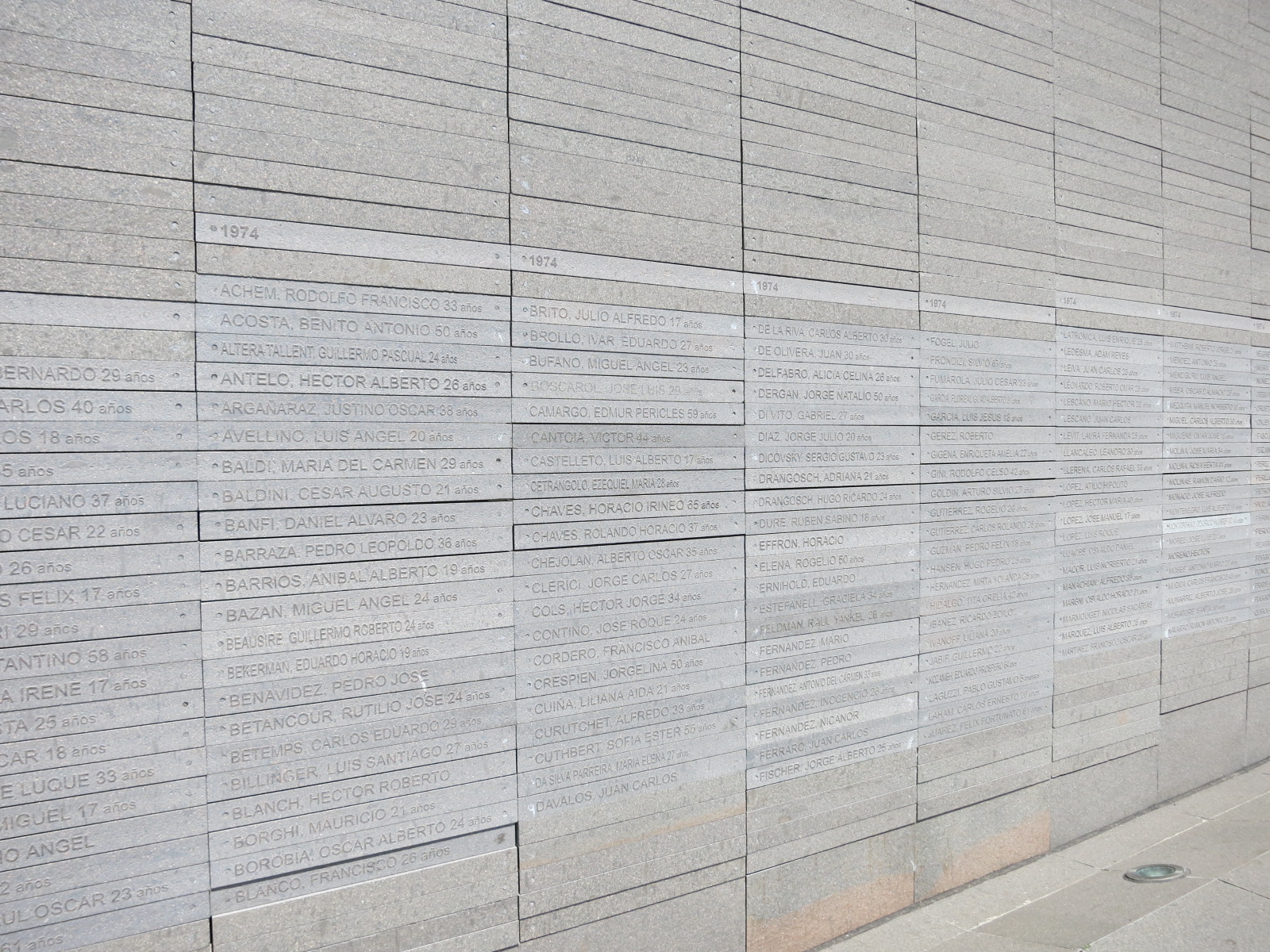

I visited as well an outdoor exhibition memorializing those killed during the period. It was a beautiful and secluded spot on the water, and each person’s name was etched in granite. Along a wall that extended. And extended. And extended. Each was listed below the year the individual was killed, and represented only those acknowledged in official statistics, meaning the actual number could have been three times as high.

I visited as well the main square, the Plaza de Mayo, the site of the May Revolution of 1810 which precipitated Argentina’s independence from Spain and the site of demonstrations which forced the release of Juan Peron from prison in 1945. (The Plaza was bombed 10 years later as part of an attempt to overthrow Peron.)

Though meals in my short time in Buenos Aires were somewhat celebratory, the rest of my time was far more sober.

- You can join the 40,000+ people who see these deals and analysis every day — sign up to receive posts by email (just one e-mail per day) or subscribe to the RSS feed. It’s free. You can also follow me on Twitter for the latest deals. Don’t miss out!

You could have saved yourself the miles & $ by buying Evita from Amazon.com. If you had watched Evita yesterday, you learned all its past. Watch it today and it’s present. Watch it tomorrow and you see it’s future. Past, present and future — all for $19.99.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s a beautiful country with great people. It’s just a political cesspool with virtually zero chance of any real improvement.

Their best hope would be to start a war with Chile, inevitably lose it and let Chile take Argentina as spoils.

@Gary

Small note: I’d disagree with your characterization of Argentina “forcing” their debt holders to take pennies on the dollar. They’re legally obligated not to offer better terms to holdouts. Since that company picked up the debt for “pennies on the dollar” (6-8% of face value, according to rumors, whereas those who accepted the restructuring walked away with 30%) from its previous owner, and the company has invested many legal resources in securing their debt, I’d say it’s more likely that the company is unwilling to compromise. That’s still speculation, though, so better to say, “Argentina and a small fraction (less than 10%, actually) of its debt holders couldn’t come to terms on restructuring old debt.”

More info here: http://www.forbes.com/sites/afontevecchia/2014/07/01/argentina-vs-billionaire-paul-singers-elliott-management-who-has-the-upper-hand/

Basically, both sides are being a little unreasonable, and from what I’ve read elsewhere, this is particular situation is unlikely to ever happen again because of collective action clauses that force holdouts in debt negotiations to accept the terms that other debt holders have accepted.

@jamesb2147 – Argentina forced debtholders to take a haircut, the degree of the haircut is the only issue with which we are quibbling. And I suppose we would also quibble over whether it is reasonable to expect to be paid back fully when you lend money or not.. 😉