Tyler Cowen reviews Thomas Philippon’s The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets. Philippon sees market concentration in the airline industry,

…we see a sharp increase in concentration in the airline industry after 2010. That is enough to trigger our interest, but not enough to conclude that competition has weakened. We must first check that concentration has also increased at the route level. We find that it has. We can further show that it came together with higher prices and higher profits.

While there’s certainly been consolidation in the airline industry as America West acquired US Airways and then American; Delta acquired Northwest; Continental acquired United; Southwest acquired AirTran and Alaska Airlines acquired Virgin America this hasn’t led to higher prices for consumers. Government should remove barriers to competition, but it’s a stretch to suggest that the several large airlines in today’s industry constitute anything close to monopoly.

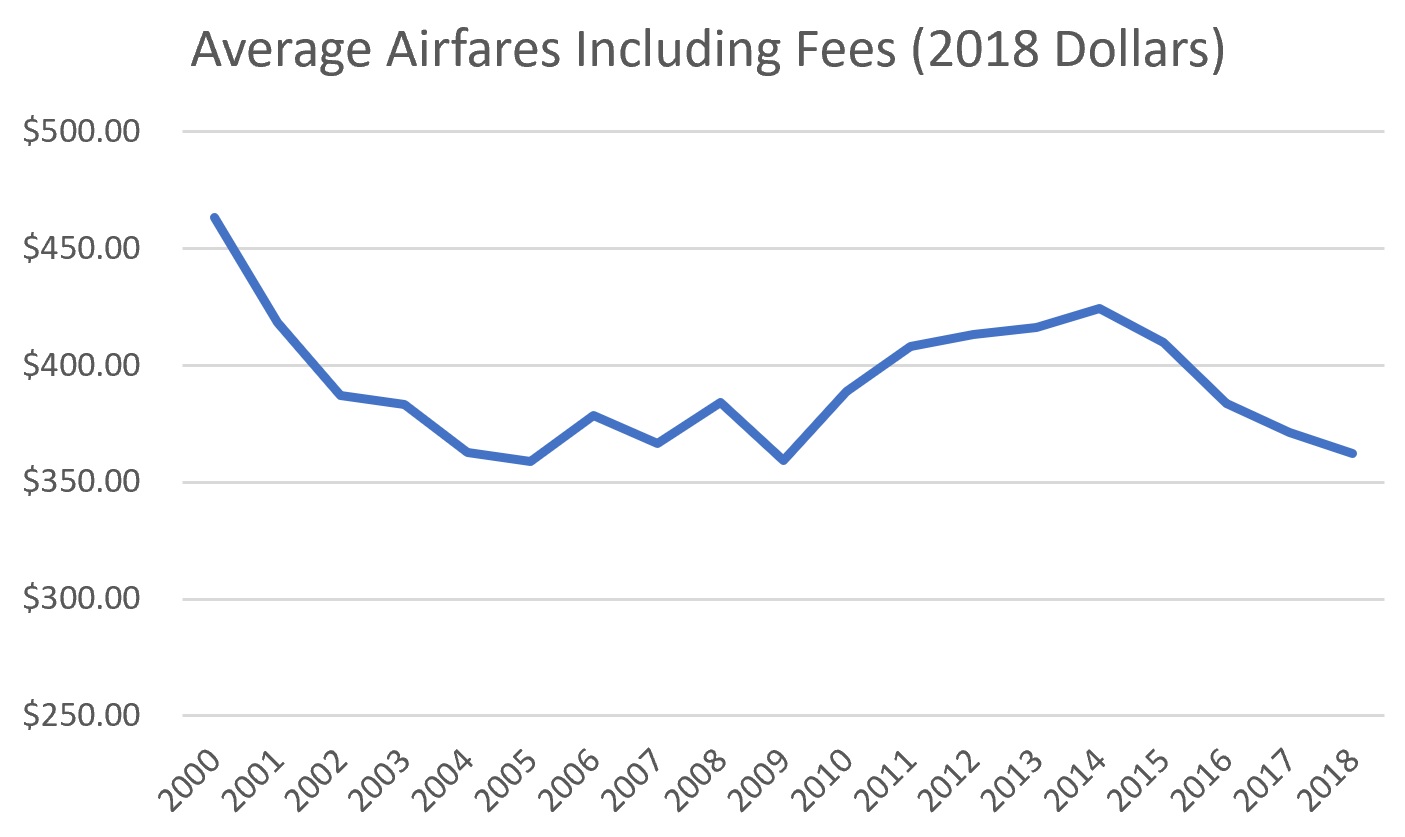

I’d point out that choosing 2010 as a starting point for airline prices – coming out of the Great Recession right before oil prices start spiking, and shortly after the introduction of first checked bag fees – is what’s doing the work here, the long run story of lower real airfares over the longer run has largely continued and first class fares are lower, too.

With oil hovering around $100 a barrel we did see airfares rise 2011-2014 but then return to long run trend, and indeed real airfares inclusive of fees were lower 2016-2018 than in 2010.

Indeed the drivers of increased airline profits are:

- lower fuel prices

- richer co-brand credit card deals.

As I’ve pointed out in many recent quarters the entirety of American Airlines profit has been accounted for by its co-brand credit card deals and not flying. The richness of these deals for airlines has grown markedly. This may be partly attributable to industry consolidation (fewer airlines for banks to negotiate with) and partly due to American Express losing its deal with Costco which set off a chain of renegotiations at higher price points.

Consolidation has improved airlines’ bargaining position vis-a-vis banks more so than consumers. And indeed with fuel prices up from three and four years ago profits are down.

The airline industry has certainly consolidated, creating stronger players that aren’t serial candidates for bankruptcy. But what’s the theory here on how many competitors can exist in a claim about monopoly? To name just a few:

- Eastern Airlines, Midway Airlines (1991, 2003), Aloha Airlines (2008), Independence Air (2009) among others went through Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

- Continental Airlines (1983), America West (1991), Pan Am (1991), TWA (2001), US Airways (2002, 2004), United Airlines (2002), Northwest Airlines (2005), Delta (2005), American Airlines (2011) went through Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Delta, United, and American are all about the same size (United has the most seats, American the most planes, Delta the most revenue in the latest quarter) while Southwest Airlines carries the most domestic passengers. And as much as I miss Virgin’s domestic first class product hasn’t Alaska’s acquisition of Virgin America just made the Seattle-based airline a more robust competitor in more markets, rather than reducing competition?

Moreover it’s the ultra low cost carriers – Spirit, Frontier, and to a lesser extent Allegiant – that have been the driving forces in the U.S. airline industry. As American Airlines President Robert Isom told employees last year,

[T]oday there is a real drive within the industry and with the traveling public to want to have really at the end of the day low cost seats. And we’ve got to be cognizant of what’s out there in the marketplace and what people want to pay.

The fastest growing airlines in the United States Spirit and Frontier. Most profitable airlines in the United States Spirit. We have to be cognizant of the marketplace and that real estate that’s how we make our money.

We don’t want to make decisions that ultimately put us at a disadvantage, we’d never do that.

Philippon suggests allowing foreign competition on U.S. routes (or foreign ownership of U.S. airlines) and I agree with this but it is insufficient to meaningfully increase competition because the scarce resource is gates and in a few cases slots at major airports.

Government-owned and run airports effectively grant perpetual property rights in gates and slots to incumbent airlines, locking out competitors. Indeed a driving force behind Alaska’s Virgin America acquisition was access to congested airports where they couldn’t replicate themselves.

@Gary FWIW, this is not uncommon in other industry verticals. I believe the correct term would be an oligopoly.

I am a little skeptical of the “lower prices” argument I constantly hear on this topic. How can one meaningfully compare prices over time when the product has changed as well? Smaller seats in everything but long haul J/F, unbundling of amenities, and cutting of frequent flyer benefits which could be seen as baked into the price of a ticket. It isn’t apples to apples over the years. Ceteris paribus, remember?

@CW certainly how you define the product matters, but unbundling is accounted for here because the prices I’m showing are inclusive of fees so it doesn’t much matter if it’s more costly to check a bag or change a ticket.

In terms of frequent flyer benefits that’s more complicated, you’d have to show a meaningful drop in real price due to the rebate with the advent of the programs **and then again with the introduction of alliance awards**, price increases for redemptions haven’t really outpaced inflation — and if frequent flyer awards have gotten less valuable I’d also point out that the programs have become more rather than less costly to offer. Although I’d agree that in the past few years specifically we’d seen reduced seat pitch.

@Ritz oligopoly should show pricing power though

I mean, you surely have an oligopoly. The five largest US carriers control about 86% of the market.

Sure, it may be appropriate to analyze competition route-by-route. When doing so, it is not sufficient to look at the number of players that are active on that route. Instead, it is crucial to look at barriers to entry and exit. If these are low, a market with just one or two carriers might still give rise to prices close to the ones that are welfare-maximizing.

In the US market, barriers to exit are clearly low. I would think barriers to entry are relatively low as well unless the route touches upon airports which are slot-deprived (e.g., JFK or DCA).

One area where the concentration of players has affected “prices” is in frequent flyer programs. With less competition, the big three have felt comfortable reducing the value of miles, in a considerable way.

Thanks, Gary, appreciate the perspective – wonder if anyone could do a meaningful analysis normalized by square inches of floor real estate?

@CW one counterpoint along those lines would be that planes weren’t as full in the past, so de facto customers got more space for their ticket in the form of a more likely empty middle seat.

@Joachim – does the number of major competitors in the U.S. constitute an oligopoly or robust competition? and how do you know? one way surely is pricing power, and the data seems to suggest airlines in the U.S. lack it.

Such an easy issue, LOL. The airline industry is an oligopoly not a monopoly. Market power ( a better term than monopoly power) is concentrated in three large carriers. The Big 3 use their market power to affect price by controlling capacity.

A major problem for airlines before mergers was excess capacity. Airlines tried to increase market share by increasing capacity and lowering prices to levels at or below cost to fill planes. With only three major airlines, maintaining capacity discipline and a healthy (and seemingly ever widening) spread between cost and price is now doable.

Airlines are recording absurd load factors. In the three months ending 6/30/19 American’s load factor was 87.5%. Thanks to capacity discipline, airlines are making record profits even though prices are said to be falling. Tacit capacity collusion is working very well for the airlines.

Lower price by itself doesn’t get airlines off the hook. In a competitive industry price = cost. Higher profits since the airline mergers are the biggest indicator of market/monopoly power. Plus the airlines have exercised their power in other ways — frequent flyer programs which are part of the competitive terms in the industry. The lock-step devaluations in these programs evidences collusion to raise price.

As I’ve stated in previous comments, not all mergers are bad. Some have pro-competitive effects. I pointed to Alaska/Virgin America. Gary agrees. That merger created an airline with the scale to compete against or at least not be crushed by the Big 3 as Delta tried to do to Alaska in SEA. Now Delta seems to be trying the same thing with Jet Blue at BOS. Delta will soon have 200 daily flights from BOS. A merger between Alaska and Jet Blue would increase competition in the industry. Alaska is the major holdout on the collusion to devalue ff programs. The Big three would love to get rid of pesky Alaska or force it into the fold.

@CW A confounding factor would be inventions like the slimline seat, which theoretical offer the same space per passenger albeit at the cost of comfort. You’d also have to work in service and reliability: are prices falling because there’s less space or because more people give up and drive moderate distances? However interesting it would be, I doubt you could get a meaningful model.

As far the squeeze on the FF programs go… it’s not clear how much reduced competition has had anything to do with that. The miles based programs were *always* a proxy for other metrics that were hard to capture at the time. My understanding is that programs were miles-focused because it was easy from an IT standpoint. Back in the day, I used to fly transcons on cheap tickets a lot. Even better were the days there were lots of double miles programs. Tell me what financial sense it made for an airline to give me unlimited free first class upgrades on a $250 r/t transcon. And for that matter, grant me status based on similar financials.

I’m pretty sure that shifting the FF model from a miles based paradigm to a financial based paradigm was in the cards, consolidation or not.

Amazing. I think I agree with all the comments.

I should comment that a lawyer uses legal precedent to determine oligopolies or monopolies. Therefore, percentage of market means pricing power means monopoly/oligopoly. Sometimes, that leads to distorted results in my opinion.

The economist considers pricing and substitution impacts in addition to percent of market. In certain markets, the airlines appear to have an oligopoly or monopoly. The airlines tend to price those markets off the profit maximizing curve (ie milk the customers for every cent, bastards). Whereas certain markets, like NYC-LAX are competitive. Prices tend to be lower, almost unprofitable (see AA leaving reducing capacity in JFK and United leaving JFK altogether).

@john:

I actually don’t think it’s that easy. Competition isn’t the only thing driving profits. Other important factors like gas prices, the cost of capital, the preferences of consumers (e.g., they strongly reduced their purchases for well over 5 years in response to 9/11) matter. I guess you could also add drivers of non-airline ticket related profits to the list (perhaps that even one of Gary’s pet projects).

Another example: In my home country, Germany, ATC has been a real problem for airline’s operations. Many market observers think airlines such as Eurowings and Ryanair suffered financially as a consequence. But, of course, while constant ATC issues affect profitability, they have nothing to do with competition at all!

So I really think you need elaborate empirical approaches to measure the intensity of competition. Unfortunately, crude measures such as industry-wide profits or the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (which essentially measures market concentration) don’t provide you with a comprehensive picture.

I’m actually not a microeconomist so I don’t know what is the current best practice. But I am aware that new methods to measuring the intensity of competition within an industry often times choose the US aviation market as an application.

Will you please add a [sic.] when quoting someone who has his facts wrong? Delta is the most profitable US airline, twice as much as Spirit. Spirit does such an awful job at turning investor money into revenue that even if at times they make a higher margin they remain far less profitable than Delta. Parker,.as it has been pointed out in the comments before, had his facts wrong.

Oh, and in 2018 Sprint grew by $0.7 billion to Delta’s $3.3b. Not even close.

@Jochim, the first sentence of my comment was “Such an easy issue, LOL” (sarcasm). So we agree on that. Mssr. Leff seems to think the issue of whether certain airlines have market power turns on whether prices go up or down. I think that is a simplistic approach because market power is more than just prices. My point is that looking at profits together with industry structure tells us a lot more about market power rather than merely looking at prices. But it’s complicated.

One fact that appears undisputable is the remarkable capacity discipline the major airlines now display compared to before the last wave of mergers. The ability to control capacity/supply/output is a hallmark of market power and symptomatic of oligopoly. Gary doesn’t address that issue.

I think any objective analysis would show that the current US airline industry works pretty well for customers, workers and shareholders. It has some oligopolistic tendencies, but these are not actually harmful to any societal interest. Compared to other industries, the prices charged for airline transport seem very fair (overall, at least) and the service is reasonable. As a country, we benefit from having our airlines strong enough to compete against foreign competitors, many of whom receive huge government subsidies.

There’s been far too much consolidation in the domestic airline industry. While there’s ample evidence, one point that illustrates this is elite status. Is your elite status worth what it was a decade ago for the same amount of flying or has it been greatly devalued?

Fares may not be higher, but costs have passed on to passengers as well as disruptions and less comfortable seats.