Brian Sumers of Skift covers Stifel analyst Joe DeNardi’s continuing call for airlines to spin off their frequent flyer programs.

DeNardi argues that airline loyalty programs are often worth more than the airlines they’re associated with.

In this week’s note, he said American’s program is likely worth $37 billion, while Delta’s is $30 billion, United’s is $25 billion, Southwest’s is $24 billion and Alaska’s is $10 billion.

Often, he has noted, loyalty programs are worth more than an entire airline. As of Tuesday, American’s market capitalization was about $24 billion.

There’s no question that loyalty programs have been cash cows for airlines. They generate billions of dollars in revenue, substantially from co-brand credit card partners, and they have better than 50% profit margins.

However the notion that these programs are worth anything close to what DeNardi believes is suspect.

When I spoke with him earlier this year he acknowledged my skepticism about the growth prospects for airline loyalty programs but suggested that revenue ‘only’ needed to grow at 4% – 6% a year in order to justify valuations of 15 to 20 times earnings. (It’s this earnings multiple that drives the gap between the valuation of an airline and his valuation of a loyalty program, since the market values most airlines at a multiple of less than 10 times earnings.)

What he’s missing is that airline loyalty programs are likely to see lower earnings in the future rather than earnings growth.

- Credit card interchange rates are more likely to fall than to rise. Whether it’s because of regulatory pressure (what’s driven the reduction in value in credit card deals in Australia and Europe, unlikely from the current US administration) or new technologies that process payments less expensively, the margins on credit card transactions are reasonably likely to fall in the future.

Then we see something akin – though perhaps not as drastic as – what happened with debit cards when they were regulated by the Durbin Amendment to Dodd Frank financial reform legislation. Processing fees were capped, it no longer made sense to incentivize transactions through the network by buying miles.

- Airlines will have to spend more to retain customers, eroding margins. Banks have shown that there’s little barrier to entry in the credit card rewards game, in fact they’re competing more aggressively than ever in the premium rewards market alongside their co-brand offerings.

DeNardi suggests that spending on Sapphire Reserve cards has been disappointing for Chase, but that’s largely relative to the outsized initial card acquisition spending (when they offered 100,000 point signup bonuses and double dipping on the annual travel credit in the first year).

He acknowledges this competition, but the point is that closing the gap with bank rewards cards will be expensive, eroding margins, cutting against the argument for a 15 to 20 times current earnings valuation.

[A]irlines need to ensure that the value their co-brand cards offer consumers remains competitive. It’s clear to us that the gap has been widening in recent years – i.e. bank rewards cards are offering more value than airline co-brand cards.

Several times DeNardi has suggested that airlines spin off at least a small part of their program to test the waters and see how the market values the program, and he can’t fathom why an airline wouldn’t do that.

However doing so is an expensive and complicated proposition and necessarily changes how a program is run, with closer to arms-length decision-making and duties to the program’s shareholders first and foremost. As part of an airline it’s far less material, requiring far less disclosure, and in practice shielding the program from bureaucracy and lawsuit.

He things that “airline executives often cannot run a loyalty program as efficiently or profitably as a company specializing in the schemes.” However experience with spinoffs suggests that they aren’t run better. The efficiency and profitability argument is undercut precisely by the need to spend more competing with bank programs.

And the real world examples here don’t look good.

Alitalia’s Millemiglia is expiring everyone’s miles. topbonus was obliterated by air berlin’s bankruptcy. However if you ignore the spinoffs which were done at inflated valuations to allow Etihad to provide extra cash to the airlines without running afoul of foreign ownership rules while exerting additional control by Abu Dhabi, you’re faced with the original spinoff: Aeroplan.

As Air Canada’s 15 year contract with Aimia comes to an end, the airline is severing ties with its spun off frequent flyer program.

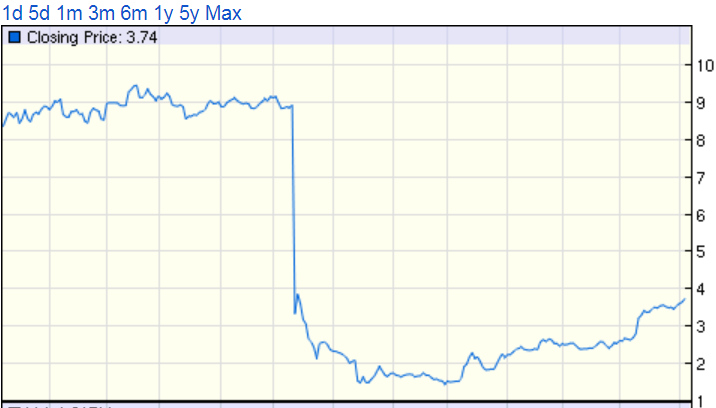

Aimia’s stock has a market cap of just over half a billion dollars. It’s always underperformed the lofty expectations the market had for it initially.

Moreover one major reason Air Canada and Aimia are in the place they are is precisely the difficulty of working with a frequent flyer program that’s a separate company. The airline’s ability to market to its customers, not fully owning its data, is limited. Their ability to treat their best customers well is limited as well, just ask a Super Elite wanting to make changes to an Aeroplan award. Want your separate company frequent flyer program to waive change fees for elites? Cough up the value of those fees yourself.

Evert de Boer thinks there are different spinoff models that might work better, but governance and control will always be an issue with an independent public company, even one still majority owned by the airline.

To be sure there’s a case for spinoffs: if an airline needs to raise cash, selling assets is one way to do that. And frequent flyer programs are in many cases among the most valuable assets an airline has. It’s just not a free lunch, selling even a part of the program creates frictions that can reduce value. Sometimes an airline needs to do that, but financially healthy airlines should be extremely cautious before doing so.

Great article. Your economics background/connections are unique here and provide valuable insight.

The Air Canada/Almia/Aeroplan saga is a good cautionary tale to any potential investor in a spun-off mileage program. Why invest in a new spun-off mileage program if there is a significant chance that it will lose all its value when it’s contract with the “home airline” expires? That alone would significantly depress the value of the spun-off company. Probably explains why Almia never really got major stock boosts, and that skepticism was confirmed when the contract was not renewed.

“There’s no question loyalty programs have been cash cows for airlines”.

I’m not sure I agree with that. Loyalty programs generate non-revenue producing passengers. will someone explain to me how this helps the bottom line? I’m skeptical that the fees paid by the bank come anywhere near the value of a purchased ticket. In support of my contention, legacy airlines have an insane contingent liability for points and like the federal debt, it is running out of control. Their solution? Make points non-redeemable and let the contingent liability continue to climb. And what does Southwest do? It deals with the issue on a ongoing basis – but at a staggering cost. By redeeming points without limitations nearly one passenger in six is non-revenue producing?

@ubuguy: Not single one is “non revenue producing”. They are using pre-paid tickets.

Very interesting article.

Qantas toys with the idea of spinning off its FF program from time to time. However it hasn’t, despite always being on the lookout to make a quick buck. Clearly the beancounters have come to the conclusion that the status quo is the best way to go, with the occasional ‘enhancements’ to irritate the active of its 10 million plus members.

I agree with the article. Particularly the business perspective that it is unlikely to be optimal for the airline to lose control of one of the key marketing tools for their product – that heavy users get what is essentially a discount – and if a business traveler, one that their company pays for, but they get to use themselves. While I mainly make my choices on flight times and reliability, and all else is pretty much secondary, I think a lot of people do make their choices at least in part to earn points, and an outside operator does not have much incentive to use earning ability to market for the airline, just to operate efficiently.

@ubuguy

AA sells its miles to third parties at around $0.012-$0.013 a piece.

AA average redemption costs (including flights redeemed on its own metal, plus redemptions on other partners) is about $0.0014 a piece.

Last year they generated around $2.5b in third party mileage sales.

And the profit from both those sales, and the deferred revenue component of the liability account meant that around 50% of their total profit last year came from the AAdvantage program.

Delta just announced yesterday that they’ll receive around $3b this year from Amex. That revenue is at around 70-80% margin.

There are no “non-revenue passengers” in this game.

Every seat has revenue attached.

@Dave F.: Interesting. Where do those per mile cost numbers come from?

Thanks.

@achalk – American’s 10Ks prior to the one filed in 2017 where most of the information got neutered.

Thks!