There’s a belief among a certain set of elites that America has adopted the aesthetic, values, and social logic of an airport lounge as its dominant cultural mode. Everything from restaurants, homes, public spaces, and even the structure of economic life has taken on the bland, frictionless, prestige-lite uniformity of the airport lounge.

- The lounge becomes the central metaphor for America’s architectural and cultural flattening, with places designed to soothe, not to express identity or history.

- Access to desirable urban life becomes contingent on holding the right financial products, not on civic membership or public infrastructure.

- Tap to pay and credit card rewards become mechanisms of soft exclusion.

- Cities like Austin, Nashville, and Scottsdale are read as interchangeable remote-first lifestyle hubs for affluent transplants, producing copy-paste “slop” culture.

In this telling, the airport lounge isn’t just a place. It’s a metaphor for a society that has decided to live in a perpetual pre-departure limbo that’s comfortable, bland, and controlled.

life in american cities will be gated behind a "tap to pay” kiosk. your ability to procure an asinine rewards card will allow you passage into safe, bland, and crowded high protein bowl based concepts. we’ve said no to the social credit score only to rebuild it privately

— Will Manidis (@WillManidis) December 1, 2025

its 2030: living in nyc costs you $5500 an hour, but its the only place you can earn $1.5m in your role as “entry level ai engineer” (net 5k a year, post expense post tax). you have no retirement, but your draftkings amex gives free helicopter rides to the airport 3 hours away

— Will Manidis (@WillManidis) December 1, 2025

Not to quibble, but this is literally the Bilt 2.0 card.

— Greg Lindsay (@Greg_Lindsay) December 3, 2025

This isn’t an original thought, or a new critique. It’s literally the thrust of Walter Kirn’s book “Up in the Air.” If you’ve only seen the movie, the main thrust doesn’t actually come through.

Kirn describes Airworld, a fully realized parallel country made out of airports, clubs, rental cars, and chain hotels. It’s corporate monoculture turned into a place, the manifestation of homogenization and alienation.

- Everywhere is the same place. Ryan Bingham lives in “nameless suite hotels,” shuttles, lounges, concourses. Cities barely register. What he really knows is club locations, security layouts, and rental counters. Geography is replaced by a network map of corporate facilities.

- Airworld has its own bland culture. Its “newspaper” is USA Today, its food is heat lamp buffet and food court chains, its entertainment is gate TVs and in-flight magazines. Nothing local, nothing rooted – just national, brand-safe wallpaper.

- Miles are pure, abstract belonging. Ryan treats frequent flyer miles as “private property in its purest form” and the true currency of Airworld. Hitting his million mile goal with a single carrier matters more than family, place, or career. His “home” is effectively his account balance.

- People reduced to types and transactions. Other travelers are sorted into categories (rookies who block the aisle, pros who glide through security), coworkers are voices at the end of a phone, and the people he fires are temporary assignments. He interacts with almost everyone through scripts and systems: boarding groups, HR euphemisms, status rules.

- Routine as self-erasure. His days are interchangeable: same wake-up in a standardized room, same airport choreography, same club, same cutlery. The very conveniences that mark him as “elite” also erase any sense of uniqueness or story.

Alienation comes from embracing this world, not having it imposed on him. Ryan has chosen Airworld over any specific place or community. The cost is that he’s disconnected from anything not mediated by a brand, a schedule, or a loyalty program. He’s proud of his fluency in that system, but underneath it he’s essentially placeless and interchangeable – a high-status ghost in a corporate machine.

In the book, Airworld is the organizing concept. It’s a quasi-nation with its own culture and currency, and the main way Kirn explores alienation. In the movie, airports and hotels are mostly backdrop. The focus shifts to Ryan’s relationships and emotional arc. The book doesn’t dwell on the structural critique of global corporate sameness.

Ryan Bingham’s written character is obviously unstable and hollowed out by his choice to live entirely in Airworld. He’s paranoid about systems, accounts, and shadowy firms. There no sense that he’s on the verge of healthy “connection.” He’s fundamentally sympathetic, if lonely, in the movie with the story framed as “can this guy learn to connect?” rather than “what does it mean to have replaced reality with a corporate simulacrum?”

The book is about a man who has expatriated into a corporate nowhere and what that does to his sense of self. The film is a more conventional story about intimacy and personal growth. Honestly, I enjoyed the film more! But this notion of alienation and corproate sameness is not new.

Max Weber argued that modernity is defined by instrumental rationality: organizing social life around efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control. Weber talks about an “iron cage” where people become trapped in systems optimized for goals they did not choose, serving structures that prioritize efficiency over meaning. This leads to dehumanization, disenchantment, loss of autonomy and value flattening.

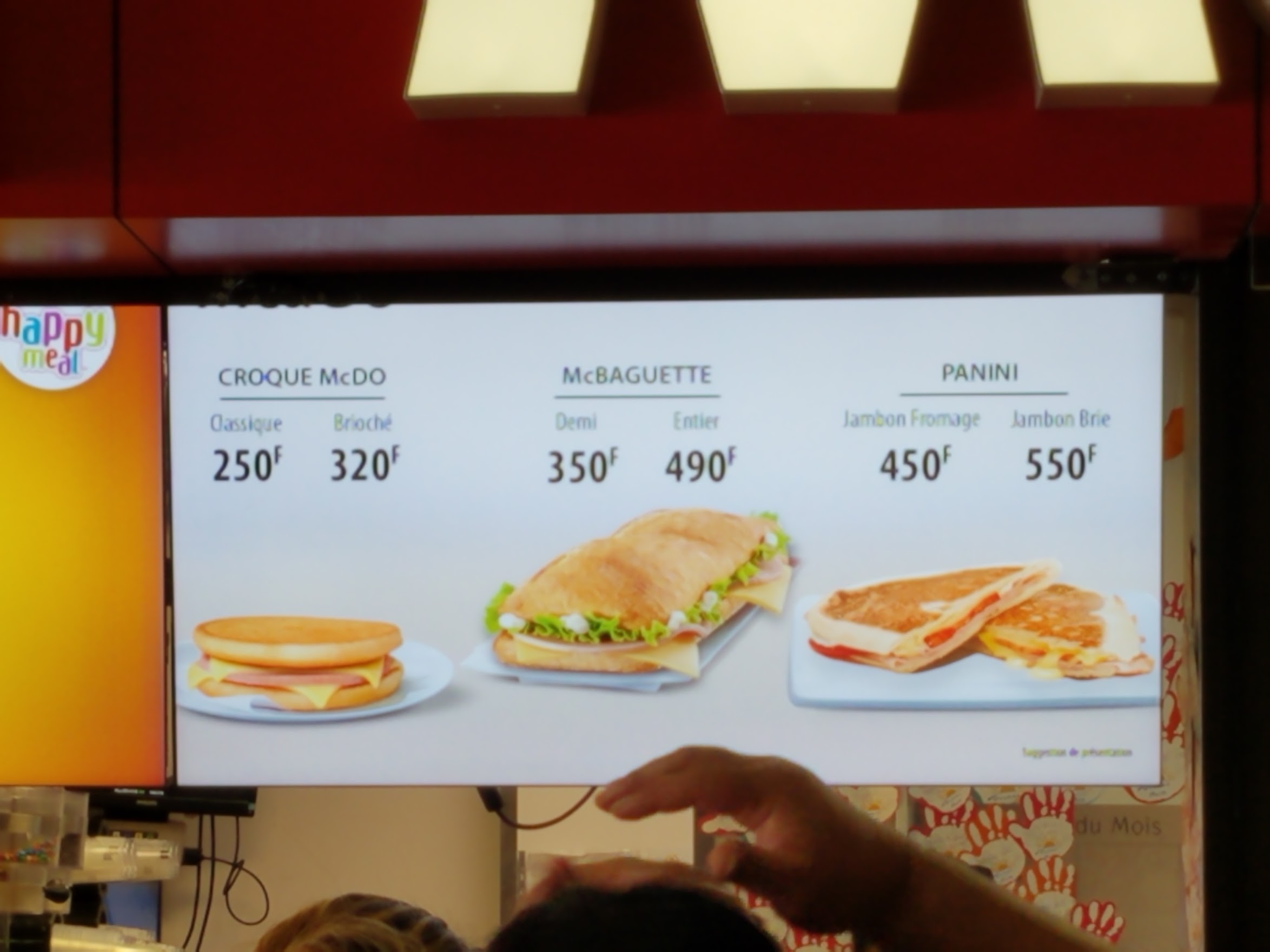

George Ritzer took this 1910’s critique and applied it to consumer capitalism in The McDonaldization of Society, corporate sameness with McDonald’s as the central metaphor, riffing on Max Weber. The world increasingly looks and feels like a McDonald’s: interchangeable, rationalized, and devoid of distinct local character.

I don’t thnk this is right, though. McDonald’s takes on a distinctly local flavor as anyone that’s seen one in India or French Polynesia can attest.

- Consumers choose speed, low prices, and predictability

- Efficiency reduces scarcity. Lower transaction costs and scale economies free up resources.

- McDonald’s exists because millions of people value affordable, predictable meals. Criticizing this as cultural decline is paternalistic, presuming consumers don’t know what’s good for them. In contrast, Ritzer romanticizes messy, inefficient, artisanal systems that priced out the poor and limited mobility.

- In fact, consumers have more choices than at any point in human history. Niches thrive online and in big cities. Consumers can spend less on baseline meals and they have more income left over for artisanal choices. How often did people eat out in the 1920s and 30s or 50s?

- Small producers now reach customers through Shopify, Etsy, DoorDash, Substack, Patreon, YouTube, TikTok. Globalization allows niche niche brands to scale and reach anyone who wants them – precisely because of corporatization and homogenization in supply chain.

Standardized coffee chains like Starbucks and Peet’s actually introduced whole generations of consumers to premium coffee and created the market for third-wave roasters. The same holds in beer, wine, fashion – and travel. Consumers aren’t trapped, they can shift to alternatives at whim.

Growing up, of course, I had Chinese food. It wasn’t very good. Mexican food was Taco Bell. Now I have easy access to Laotian and Malay food – even in a third-rate city for Southeast Asian cuisine. And not just food from Malaysia, but varietals within that (like Nonya cuisine).

In fact, so many things are better. As I finished up college I didn’t think that would be true. Life felt like Natalie Merchant’s “These Are Days” (1992) which was sung in the present tense but framed from the future: right now is the future you’ll nostalgically replay. It was about privilege and luck, not entitlement. Yet the world does keep getting better, for most people. Western corporations export their wares, but American consumers import from abroad, too.

Airport lounges themselves have actually improved. I remember ginger ale and goldfish crackers as a kid in the early 80s, a photocopier in the Admirals Club at DFW in the early 90s, and packaged Tillamook cheese in United’s Red Carpet Clubs in the early 2000’s. More people have access today and the lounges themselves are better. Even as American Express homogenizes its lounge food compared to 2014, Capital One offers José Andrés tapas in D.C. and the new Chase lounge in Las Vegas features David Chang.

And need I add that the homogeneity of airports themselves is a function of governments, rather than market capitalism? It’s governments that own the airports in the U.S. and contract for their retail experiences. Goods sold there pass through government security checkpoints, usually brought through by preferred vendors selected by the state. It’s those government entities that dictate the dinner-only ‘Japanese restaurant’ must serve the same eggs for breakfast as everyone else in the airport.

The reason, of course, that this is an elite theory is because the central problem of the airport lounge is that too many people have access.

It’s a story of aspiration and upward mobility that creates crowding at the top. Access has expanded, and that makes these spaces less elite. So the snobbish amongst us don’t like it.

This guy Manidis sounds like a real condescending pr1ck….

Gary, my first post after several years of lurking — what a fascinating read! You’ve compressed a lot to think about into few words.

It is an absolute myth that “too many people have access” to the lounge(s). It is true that – due to a variety of credit card’s – MORE people have access than say in 2010. However, look around when you leave the lounge in any busy airport (ATL, JFK, etc.). There are lines at Starbucks, lines at Wendy’s and Burger King. Hell, recently I saw a packed bar and a wait-line to get into Friday’s in ATL. Not to mention all the people sitting at the gate an hour before their flight. Those are all the folks who DON’T have access. So, while sometimes inside the “lounge bubble” it can appear that everyone in the airport can get in…they really can’t.

A lot of elitist mumbo jumbo in that article. Condescending elitists are gonna condescend. They think they are better than you. It is a form of bigotry.

Good article in the December 1st “New Yorker” magazine on the history of airport lounges. Also it compares many of them–the author tried to go to every one in the New York area. Readers might enjoy it.

America as an airport lounge? Don’t see it at all. Unfortunatley (as an admirer of America) today it is more like Spirit airlines…A chaotic space, surely spiraling down into some kind of dissolution (how that takes form in reality is yet to be seen).

What’s really happened here is more of a microeconomics lesson on equilibrium than anything else. Once credit card companies entered the lounge market, they quickly realized that a lot more money could be made by charging more people less money for access. Hence, it no longer made sense from a profitability perspective to keep the rates unobtainable for a large percentage of the flying public.

If you’re not wealthy enough to fly private, yet wealthier than most of the lounge credit card holders, one great solution is to pay for the VIP services available at many key airports. These typically come with a completely private furnished room, full catering, private security screening, and a dedicated vehicle to take you directly to the aircraft when it’s time to board. Of course, not every airport has such a service, but many do.

Forget the creature comforts, the US has been run by the airport lounge population for the last few decades

The also was a time when air travel itself was considered a luxury. Living it the nation that gives all of its citizens the ability to be upwardly mobile has it’s drawbacks. Personally I fail to see the need for lounge access. I plan my travel to spend as little time as possible in airports. I can fly through security thanks to Pre-Check and smart packing. I connect in CLT a lot, never book less than an hour connection, never seem to need more than 2. Why would I need a lounge?

@drrichard — Speaking of the New Yorker, excellent free exhibit at the New York Public Library (5th & 42nd) now through February 2026 on a Century of the New Yorker.

I dont know about lounges signaling status in the past

In 2005 when you walked into fancy named Red Carpet Club or Presidents Club, you’d be greeted by packaged cheese and mini carrots.

The clientele would be sad looking middle aged men who were flying for work, maybe making 30k a year presenting PowerPoints or selling car parts

Hardly people that represented ‘status’

@1990 – great suggestion!

Bill J is spot on.

spot on. what’s even more disturbing is that some restaurant and retail establishments now have spread nationally taking even more of the local flavor away

After not having been to lounges for a bit I visited one twice recently since my trip coincided with my brother in law’s on two occasions and he’s a big lounge guy.

The food there was ok, drinks were fine: I don’t require anything fancy anyway. As it happened a lady ordered an Aperol Spritz and I had to order it myself since it reminded me of downing quite a few in Italy a summer ago.

As someone else mentioned I’m usually just cutting it close while on business trips, only trying to get there early enough to not have to check in my carry on. So I never get time to visit a lounge and after this couple of occasions, I simply don’t think it’s worth my time.

The part about making the everyday experience in America very generic is true though. While there’s some regional variations, it’s becoming more and more uniform.

@Peter — Yeah, there’s still loads of ‘free’ interesting things in the city that even locals might like; even though they close at 6PM on weekends, last entry to the library is 5:30PM (learned that the hard way). Speaking of NYC, wild ‘first snow’ (eh, more of a dusting) overnight Saturday morning.

I live overseas, and the minute I return to the United States I see a lot of jerks everywhere.

@KPR — Have you considered that if everyone’s a jerk to you… maybe… hear me out… you, in fact, could be the jerk? Naw, you right, it’s everyone else. Phew!

He probably has a Amex Plat card. The irony.

Lounge food and drink have improved because the lounges need some incentive for people to sign up for a $600+ plus a year credit card. I would bet that on any given day in a typical lounge (not a class of service lounge) that most of the inhabitants fly less than 6-10 times a year. Some of the behavior I’ve seen in lounges is complimentary to the Spirit Airlines lifestyle.

I find that a quiet, unused gate is a much more comfortable place to kill time than most airport club lounges.

False dichotomy — expanded access or cultural decline. Mass culture is neither good or bad. People should do what they want, albeit choices may be limited. Greatest good for the greatest number is now a conservative idea. The most annoying parts of this are Gary’s inexplicable fixation that life is getting better (which is not on point) & our local man of people advising as to an exhibit about the New Yorker.

“There’s a belief among a certain set of elites that America has adopted the aesthetic, values, and social logic of an airport lounge as its dominant cultural mode. Everything from restaurants, homes, public spaces, and even the structure of economic life has taken on the bland, frictionless, prestige-lite uniformity of the airport lounge.”

Ridiculous drivel. We’re copying the airport lounge? Not the other way around?

“Standardized coffee chains like Starbucks and Peet’s actually introduced whole generations of consumers to premium coffee and created the market for third-wave roasters”

Gag! Gary, you should be ashamed for saying Charbucks introduced consumers to premium coffee. Like Micky D, it’s everywhere, but not good.

@Anna — I remember the USA airline lounges of 20 years ago and I think you are spot on about the food, but not entirely correct about the clientele. While there were many “middle class” salesman, they were also plenty of corporate executives there too. It was businessmen (few businesswomen) of all stripes. The typical guest was in a suit. I don’t miss the bad food and mediocre beverages, but I do miss the lower crowd levels than we see today. Just a different era, I suppose.

What a load of crapola.

First of all I AM an elitist, but I do NOT belong to any airport lounge because I AWAYS fly first class or private (also a 2.5 million mile member of Oneworld). So when I fly business/fist overseas I get free access anyway.

I live in San Diego, so I get to the airport exactly one hour before flight time, go through pre-TSA, and seldom buy any food – I have decent food at home (live 10 minutes from the airport) before I fly. I find some unused gate, and do a few emails before flight time. If I have a connection at DFW, etc. I try to book a short one, but if not, I use the time to get exercise walking from one gate to another – even if 45 minutes.

I have some friends who post pictures from the airport lounge, as if they are first-class, but then they fly low end airlines like Spirit, or the back of the plane on American. Lounges are just a status symbol for wealthy wanabees. . .actually real wealth flies private these days.

Speaking of jerks….funny that @1990 couldn’t resist the urge to respond to an observation with a nasty snark.

@1990 is DEFINITELY not a jerk. He said that once.

@Marikinsandiego

“I am very rich…but I am here on a mediocre blog.”

If you feel condescended to after reading this article then you are exactly the person who lives in that bubble you wish not to be able to see out of. After spending 3 years living in SE Asia this view of the US is spot on. The sanitized dullness of American culture is excruciating, especially from afar. Despite a high standard of living in the US, there is a low level of happiness. I live in Bali, Indonesia and Australia before that but I’m American. I don’t have any bone to pick with my home, i just finally realize that the monotonous cut and paste of every town and city in America is on purpose and it isn’t necessarily what Americans want, it’s simply what we got because it’s easy and it makes money. If I were to bring the average 25 year old Balanese young adult to the average mid size American city they would be astonished at the wasted space, the painful orderly lines and flow of everything that would seem like dystopianscience fiction. Americans think they live in the “freest country in the world” when in reality they live in stifled, rule and law driven prison where you are constantly looking over your shoulder, minding what you say and hoping you don’t offend someone for something you say, do…avoiding places that are unsafe, many carrying guns for self defense. Things that are absolutely unfathomable to young people in most of the rest of the world. It’s hard to come home these days but it’s wonderful to see family. Increasingly they come to Bali, while not perfect, Indonesia certainly has it’s issues but the tight knit, friendly, welcoming, kind and accepting people of Bali, regardless of their age is something you do not find in the US anymore. It makes me a happier more content, healthy person, qualities most Americans desperately need more of.

Looks like “Generica” has reached it’s pinnacle.

@FlyOften — Finally, someone else gets it! Gotta out-jerk the jerks. So much jerking going on around here…

Starbucks and Pete’s created the market for small roasters? No way. Starbucks literally monopolized on a trend that was already happening. My city had several local coffee shops and roasterys before Starbucks moved in across the street from them and undercut their prices. Starbucks couldn’t open for almost 2 years because people would keep breaking their plate glass. I don’t know where this “read” comes from, and I’ve seen it often. It feels too much like, thank the corporate overlords for everything we enjoy. It’s just not true. They are vampires not creators

Last time I was in an airport lounge or wasn’t 1/4 foreigners imported by jews to work our jobs for 1/2 the wages, no loud blacks smoking weed and shooting up the place, and the drinks were free.

It was nothing like America. At least not since the Great Replacement began, the country Boomers lived in.

@Todd,

Spot on my friend.

@Todd — So, you’re one of those ‘passport bros’ living in SE Asia, eh? No doubt, Bali is nice. Grateful to have visited a several times, but, not sure I could ‘live’ there. It’s just not a ‘serious’ place, unless you are in the tourism/hospitality industry. Ok, fine, if you’re retired, and looking for a place to live ‘on the cheap,’ yes, you can find some spots in SE Asia, so long as they let you live there, and you adhere to their local laws and customs (Bali is notorious for strict adherence to certain ‘rules,’ lest we forget). But, get real, DPS, and other Indonesian airports are not much better or worse than US, European, E. Asian, or even Australian airports. Like, is that ‘updated’ Blue Sky Premier lounge really that ‘great’ (oh, it’s got a chocolate fountain, and Bali High beer… psh.) So, no, @Kevin, not the spot. We’ve got the equivalent of Bali in Hawaii and Puerto Rico, yet, folks whine about those places, too. The grass is always greener. Gotta find happiness wherever you are; doesn’t need beaches or volcanos; for some, it’s in a city (I know, crazy).